We have a king, and his name is Charles - Prince Charles, if you must know, which I can't stop calling him. Remember as a child forgetting the new year had come, and by sheer force of habit, writing the old year in your jotter on your first day back at school after Christmas? Well, it's like that.

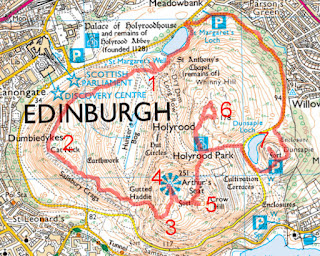

But though I'm not one for royalty, even I was aware of Charles' big day yesterday, with all the pomp and tradition of hundreds of years. There's the ride in a gold coach, Zadok the Priest, anointing by the archbishop, carrying the sword and sceptre and orb and wearing the crown. And there's something else he did, something that caused a lump of Perthshire sandstone to be taken out of Edinburgh Castle a few days earlier and be transported to London. The stone is the Stone of Destiny, and it had to be in Westminster Abbey specifically so Charles could sit on it. I'm sure the coronation would still be valid without it, but the stone is one of the oldest parts of the ceremony, having been in London since the late 13th century.

Or has it?

The twist is that after being damaged during the 1950 heist, the stone went to a stonemason's yard in Glasgow for repair. And that mason, Bertie Gray, made two copies. According to the Reverend John Mackay Nimmo, Chevalier of the Knights Templar of Scotland, it was one of these copies that went back to London in 1951, and the real stone hidden in a location that he alone knew. When the Scottish Parliament recovened in 1999, Nimmo offered his stone to the nation. X-ray analysis showed that Nimmo's stone was not broken and repaired in a way consistent with the stone taken in 1950, and it subsequently disappeared from view.

Well that's a nice story. A quirky anecdote for something that was definitely taken in 1296 by Edward I, and definitely taken back again in 1950. That must be it, surely? No! Strap in, because the Stone of Destiny has more legend and myth attached to it than anything else in Scottish history.

Other legends go back to 1296 and the original theft of the stone. Knowing Edward was coming to steal it, the monks of Scone swapped it for a worthless lump of local sandstone - reputed to be a cludgie cover - and hid the real thing in a nearby hillside. And there it sits, hidden to this day, awaiting its moment... or perhaps not! Because Robert the Bruce found and used the real stone, according to another legend, and entrusted its keep thereafter to Angus Og Macdonald. It's actually hidden somewhere on the Isle of Skye, its whereabouts known only to the chief of the Clan MacDonald. Why else would the Scots not have demanded the stone's return from London after the Bruce's victories? Because they knew the one in London was a fake.

Ach no, say the people of Argyll. The real stone - the actual, proper Stone of Destiny - still lies in Argyll, somewhere near Dunstaffnage Castle, brought over when the Scots first migrated from Ireland. Whatever the Scottish kings were crowned on at Scone in Perthshire, it wasn't the real McCoy.

Head spinning yet? Don't worry. The Irish have a story to resolve the mystery. The Stone of Destiny - originally the Irish Lia Fail - never left Ireland in the first place. A switcheroo saw the Scots sail off to Argyll with a fake, as the real stone, its origin the Holy Land rather than Perthshire, still lay under the ground of the sacred Hill of Tara.

(For more detail behind these legends, the best read is Stone of Destiny by Pat Gerber.)

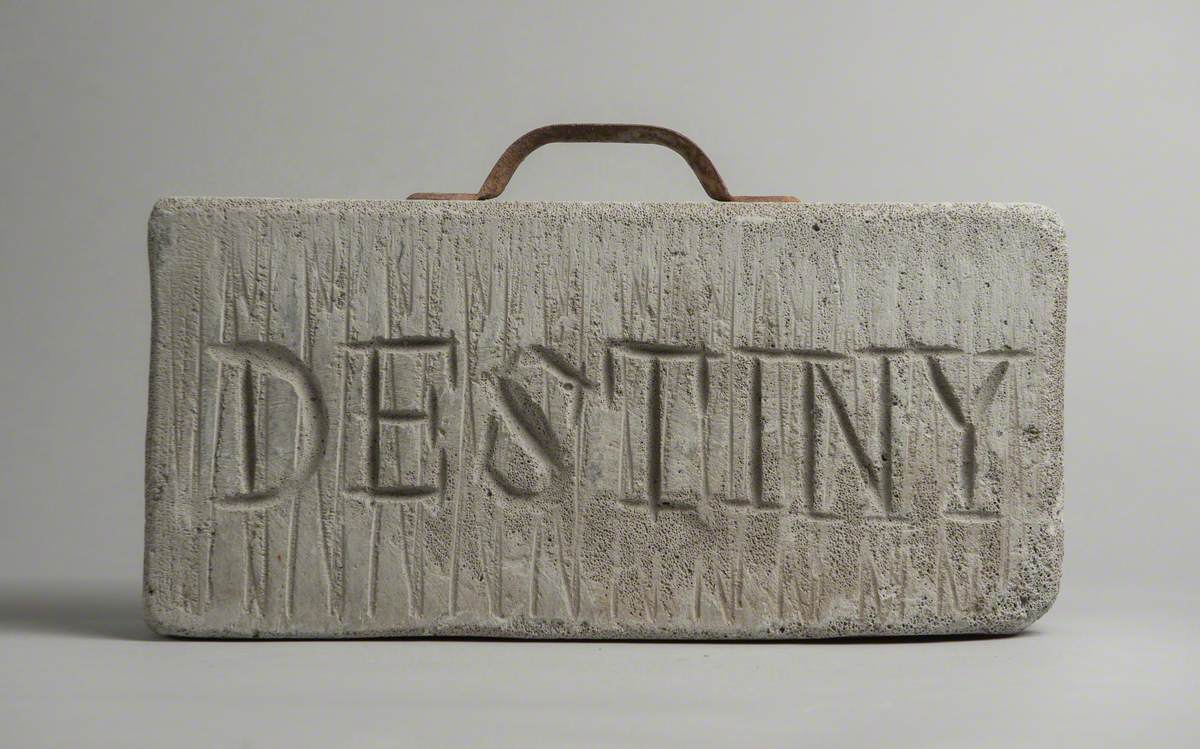

The Stone of Destiny fairly gets about. Its travels inspired scupltor George Wyllie to create portable 'Destiny' stones the size of briefcases, with a convenient handle for anybody to carry about. And that inspired the closing lines to my poem 'The Stone Room':

For boys of destiny

still play under Argyll skies -

freedom is a noble thing.

I found myself some bedrock

and in time-honoured tradition

have proclaimed myself a king.

.JPG)